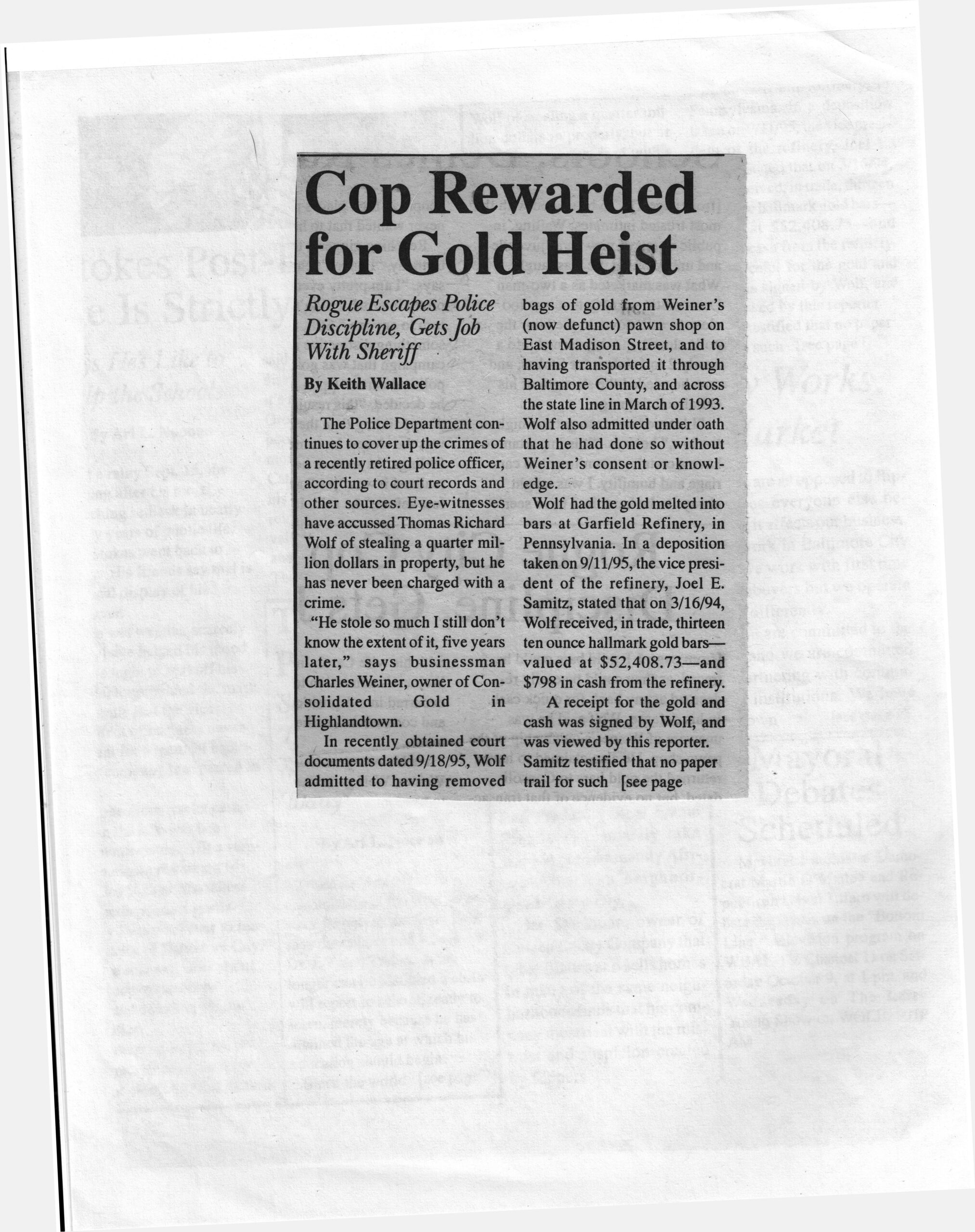

Rogue Escapes Police Discipline, Gets Job With Sheriff

The Police Department continues to cover up the crimes of a recently retired police officer, according to court records and other sources. Eye witnesses have accused Thomas Richard Wolf of stealing a quarter million dollars in property, but he has never been charged with a crime.

“He stole so much I still don’t know the extent of it, five years later,” says businessman Charles Weiner, owner of Consolidated Gold in Highlandtown.

In recently obtained court documents dated 9/18/95, Wolf admitted to having removed bags of gold from Weiner’s (now defunct) pawn shop on East Madison Street and to having transported it through Baltimore County and across the state line in March of 1993. Wolf also admitted under oath that he had done so without Weiner’s consent or knowledge.

Wolf had the gold melted into bars at Garfield Refinery, in Pennsylvania. In a deposition taken on 9/11/95, the vice president of the refinery, Joel E. Samitz, stated that on 3/16/94, Wolf received, in trade, thirteen ten-ounce hallmark gold bars— valued at $52,408.73—and $798 in cash from the refinery.

A receipt for the gold and cash was signed by Wolf, and was viewed by this reporter. Samitz testified that no paper trail for such gold bars could be traced, as they could be easily redeemed at any bank for quick cash. In his defense, Wolf said he was unaware of Weiner’s ownership of the pawn shop. He also claimed to have returned the gold bars to Consolidated, but no evidence of that transaction has surfaced.

Three months after his testimony, Wolf retired from the city’s police force with a full pension, and stepped into the director’s position in the K-9 division of the Baltimore County Sheriff’s Department. The Baltimore Police Department refuses to release documents regarding their investigation of Wolf. Originally denying knowledge of the documents, Police Department lawyer Sandra Holmes spoke of “grave reservations” about the content of Wolf’s file and denied its release on October 6th.

Other sources confirm that in May of 1994 Police detective Joseph Adams, of Internal Investigations Department, headed the investigation of Wolf, and interviewed Charles Weiner at least six times over the course of the month, including once over lunch at the Eastern House, a longstanding eatery in Highlandtown. Wolf was eventually charged with having sex while in uniform (with Weiner’s wife Robin), but not with theft.

The Weiners have since divorced. The court documents used in this article were taken during that trial. In their depositions, R. Weiner and Wolf admitted to having conducted an adulterous affair. Wolf resides at Oak White Road, in Baltimore County, with his wife Carol. Incidentally, R. Weiners’s admission to the affair occurred in a deposition held this year, and contradicted earlier sworn statements.

Via his two-year liaison with R. Weiner, Wolf gained unlimited access to company safes and storerooms and—along with the bags of gold— smuggled out vast quantities of jewelry, appliances, and tools from the shop, say former employees of the store.

Shelley Collins—who had been R. Weiner’s friend for thirty year—was the pawn shop’s bookkeeper. On 7/5/ 95, she testified against R. Weiner in Circuit Court. She stated that R. Weiner was smuggling out gold from the pawnshop, and funneling the proceeds into her personal bank account. Collins also confirmed that many appliances and tools were stolen from the shop. She specifically implicated Wolf in the thefts.

Both Wolf and R. Weiner have since disputed Collin’s testimony.

On May 17th, 1994, Employees at the Madison Street pawn shop made the following recorded statements to an investigator hired by C. Weiner:

“I would go down to the basement and there he [Wolf] is digging through a box and takes and puts everything into a brown bag, okay, and takes it upstairs. He took portable CD players, portable radios, I mean he’s taken television sets, he has taken tools, I mean that man has taken so many tools out of that place, I couldn’t count anymore, an he just takes it in a bag” Ken Emerson.

“He [Wolf] took out a whole carload of expensive tools from the basement [in February 1993]. They jam-packed his car full.” Theresa Powell.

“The employees have gotten to where we would hide things, if it was something really good that came, we would hide it. There wasn’t a day that went by that Rick [Wolf] didn’t walk out of here with something good.” Janice Emerson.

In October of 1994, R. Weiner called the city police department’s Evidence Control twelve times, according to her phone bill statement. Each call lasted up to 17 minutes. In his deposition, Wolf acknowledges that “I have no reason to be there whatsoever.,.1 don’t want to get involved in that one. I don’t know.”

The States Attorney, Haven Kodak, declined to press felony charges against Wolf in 1994. “We could not prove that a theft had been committed,” said Kodak recently. He said that, because Weiner’s wife was the manager of the pawn shop, his office could not have proven the case beyond a reasonable doubt.

According to Weiner, he was also contacted by the office of Michael Gambrill, who was then the Baltimore County Police Chief. “In order to avoid embarrassment to the city, we will let Wolf retire,” Weiner recalls being told. “This wouldn’t be the first time,” said a well-placed source in the city police department.

Almost immediately after her recent election, Baltimore County’s new Sheriff, Anne Strausdauskas, got rid of Wolf. “We had a difference of opinion,” she said, “if I had been Sheriff [when Wolf was hired], and came across this, I would not have hired him. No one is above the law.”