Gardening on the East Coast presents a unique set of challenges, including dealing with humid summers, hard freezes, and late frosts. The idea that tropical plants, cacti, or succulents thrive effortlessly in this climate is a misconception.

Instead, successful gardening in this region demands a gardener’s willingness to observe their microclimate closely, choose plants suited to that environment, and adapt as needed. This approach contrasts sharply with the notion of “hands-off” gardening or plants that “survive anything” often showcased on Pinterest.

Climate Zones: A Path to Understanding

Thankfully, navigating these gardening challenges isn’t as daunting as it might seem. One key parameter can simplify this process: understanding your garden’s climate zone.

The East Coast predominantly features a continental climate, characterized by moderately warm summers and winters cold enough to freeze the ground for extended periods. This climate knowledge is crucial for selecting the right plants for your garden.

The USDA’s Plant Hardiness Climate Zone Map, updated in 2012, serves as an essential guide for gardeners and growers. This map categorizes areas based on the average annual minimum winter temperature, aiding in plant selection.

A convenient zip code lookup tool on the USDA’s website allows for precise climate type identification. For instance, New York State’s climate zones range significantly, impacting which plants are best suited for different areas.

Your Garden’s Uniqueness

It’s important to recognize that individual gardening spaces may deviate from their general climate zone due to various factors like soil type, drainage, and exposure to sun and wind. Urban areas might experience higher climate zone numbers due to reflected light and heat from buildings and asphalt.

Recent research indicates a shift toward warmer winter temperatures and suggests that USDA plant hardiness zones may move northward due to climate change. This underscores the importance of closely observing your garden to understand its specific conditions and selecting plants accordingly.

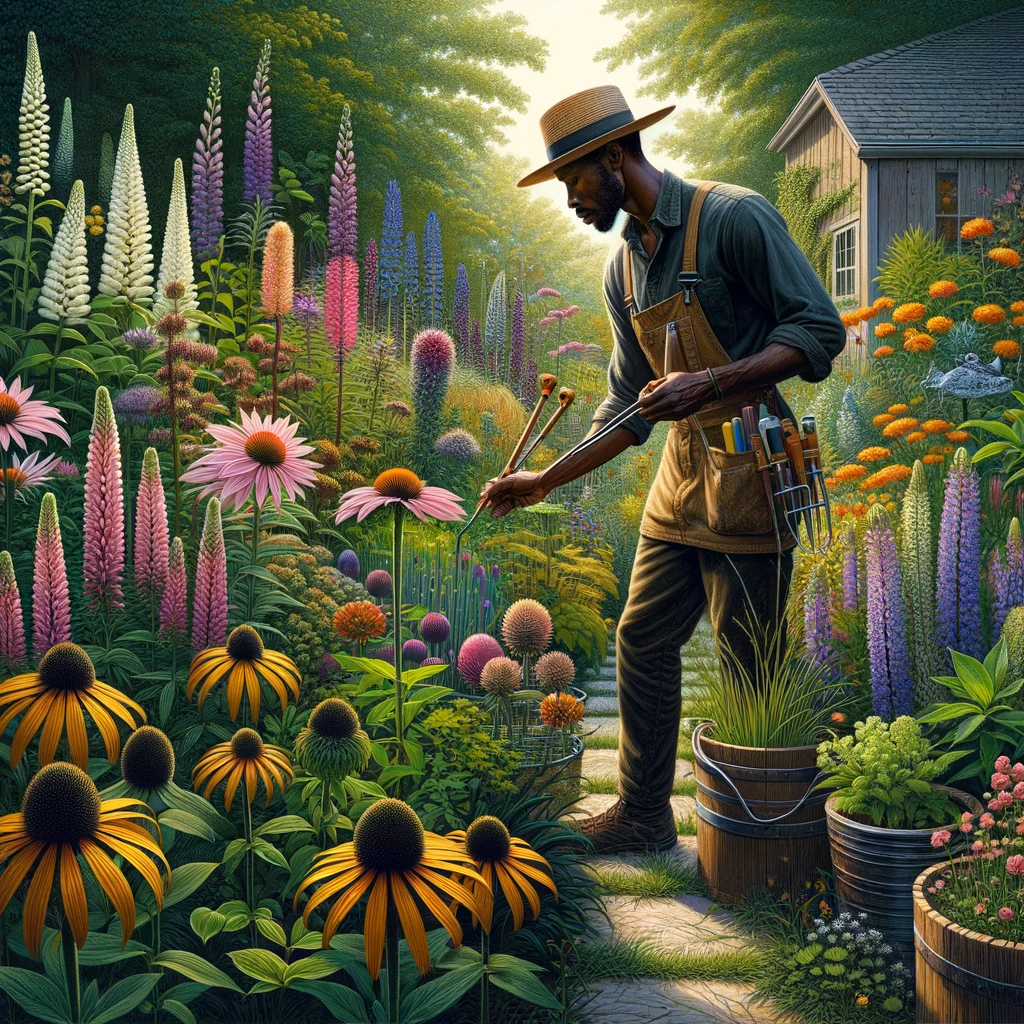

Embracing Native Plants

After familiarizing yourself with your garden’s Hardiness Zone, consider the benefits of native plants. Choosing native species helps preserve local ecology and offers a sustainable approach to gardening. Avoiding invasive species and focusing on native flora can significantly enhance your garden’s health and beauty.

This comprehensive approach to gardening on the East Coast highlights the importance of adaptability, observation, and a commitment to environmental stewardship. By embracing these principles, gardeners can create thriving gardens that reflect the unique characteristics of their local ecosystem.